Contents of Old Trunks Restore Family History to Local Author

Like many of us, Greta Nettleton did not know very much about her father’s family and there were no surviving elders who could tell her their stories. Greta and her sisters lived a life without a past. And so things were until Greta’s mother moved out of the family home. In cleaning out the house, Greta and her sisters discovered a number of old trunks in the attic. In the interest of just getting the work done, the sisters suggested the trunks go to the dump, but something about the trunks spoke to Greta and she offered to take them without knowing what was in them. They sat in her house for a number of years until one day she opened one and found that her father’s grandmother, Cora Keck, had preserved diaries, scrapbooks, photographs, letters and other memorabilia for her father. He had never opened them nor had spoken about them.

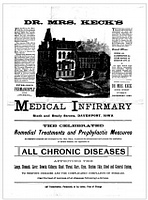

The trunks contained a treasure trove. Much of the material was about her great-great-grandmother, a Mrs. Dr. Rebecca Keck, described in her 1904 obituary as, “for nearly thirty years a practicing physician in Davenport [Iowa]” who “had one of the largest infirmaries in the state.” Greta discovered that Mrs. Dr. Keck was a pioneering practitioner of medicine and a major, controversial participant in the struggle between the socalled ‘legitimate’ physicians and those who, like her, were not certified or formally trained, over who had a right to practice medicine. Mrs. Dr. Keck was the only woman other than Lydia Pinkham who made a fortune and had a substantial reputation in the patent medicine business.

Because of her enormous success, Mrs. Dr. Rebecca Keck and her Infirmary for All Chronic Diseases became highly visible targets for the medical establishment in Iowa and Illinois. Doctors assaulted her integrity as well as her legitimacy, branding her a “quack” and repeatedly prosecuting her in the courts, but she had such strong support from her clients and the press that she was able to persist in calling herself a physician, and run her business profitably until she retired in 1900.

In the interim, her daughter Cora, Greta’s great-grandmother, was sent to Vassar College with the objective of conferring respectability and social legitimacy on the family by acquiring refinements and marrying well. The diaries and scrapbooks in the trunks belong to Cora.

Cora, it turns out, was far from the meek, obedient daughter of a dominating business woman used to getting her own way. Once away from home, she broke loose. She had romantic flings with her female classmates - she kept a photo of herself in drag - and ran with a fast, artistic crowd, sneaking out the window of her dorm to take trips to New York City, smoking cigarettes, exhibiting a mordant sense of humor. She was a highly gifted musician; it was at Vassar that she discovered her talent. For her graduation recital, she played a piece by Liszt of “conspicuous technical difficulty,” reviewed by The New York Times as “the gem of the evening.” She was invited to perform with the musicians of the New York Philharmonic.

Her mother frowned on Cora’s musical ambitions and did what she could to squelch them. At that time, respectable women could not appear in public performances. Mrs. Dr. Keck did allow Cora to play the banjo at church fundraisers in Davenport, a paltry and sad compromise. The tension between mother and daughter peaked when Cora eloped with one of her mother’s business associates, a man forty years her senior. The rift was healed when Cora’s own daughter, desperately ill and not responding to “legitimate” medical regimens, was successfully treated by Mrs. Dr. Keck and the child’s life saved.

For the last several years, Greta has been researching the historical background of her family’s history with support from Vassar College. Greta has nearly completed the first of two books she plans about her remarkable relatives. The first is called The Quack’s Daughter, about Cora and her efforts to make a life for herself in the constraining and rapidly changing social milieu of Victorian America; the second is called The Charmed Line, about Mrs. Dr. Keck and the window her career opens onto the turbulent beginnings of modern medicine. A chapter from The Charmed Line will soon be appearing in the State Historical Society of Iowa’s flagship publication, Iowa Heritage Illustrated. Greta is developing an author website about both books.