The Divine Proportion: The Art of Harriet Hyams

“Build thee more stately mansions, O my soul…” From “The Chambered Nautilus,” Oliver Wendell Holmes Visiting Harriet at her home in Palisades is what I imagine it would be like to enter one of her stained glass works, if such a thing were possible. The angular house evokes the abstract, featuring space both negative and positive, and kaleidoscopic light filtering through the tree canopy and reflecting off the painted walls as the sun progresses across the sky. We enter a place where, as Harriet has said, life and art are inseparable.

It has been Harriet’s mission over her long artistic career to demonstrate this truth wherever the opportunity has presented itself. She began with painting, the paint getting thicker until she was using a palette knife; then came clay, carving, and welding. She had been welding for about ten years, playing with fire, as she puts it, when she noticed the light coming through the visor of her helmet. She wondered about adding glass to metal. She experimented for awhile, but it wasn’t until a colleague suggested she go to a stained glass studio—the Greenland Studio on West 22nd Street in Chelsea—that she found what she was looking for: natural light passionately transformed by configurations of glass.

Harriet learned her art by visiting dozens of European churches and synagogues and working with glass importers. Because 98% of stained glass windows in Germany were destroyed in World War II, post-war artists working with the German government had the opportunity to develop a modern aesthetic. She met and befriended the great German artists, who had an indelible influence on her work, and the American Robert Sowers, who designed the famed American Airlines window at JFK airport.

Her experience working in a masculine space, as sculpture was previously considered, with the feminine emotional range glass provided, taught her how to negotiate the gender expectations of both the religious and secular world. All her commissions came to her by word-of-mouth; she never had an agent. Her ability to understand the sensitivities of others not remotely like her allowed her to prevail in almost allegorical situations, like the time she was asked to wait in the dark before interviewing with a committee of men in a well-lit room while their wives worked in the basement kitchen.

Her first job was designing the windows for Temple Emeth in Teaneck, New Jersey where she is a congregant. She’d never done anything like them before, but the architect, Percival Goodman, believed in her abilities. The windows were an immense success. From this triumphant beginning, Harriet went on to design glass for the Jewish Chapel at West Point, the Dominican Chapel of Our Lady of the Rosary in Sparkill, and the world headquarters of Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, among others. Many pieces are in private collections. She's had over fourteen solo exhibitions, selling almost all of her works and winning numerous awards.

Harriet believes “there are times when themes, places, and organizations fall into place without a struggle.” This was true for a project honoring her parents, Maurice and Syd Krivit, and Senator Robert Menendez, with a pair of windows in the new Jersey City Medical Center building. She chose the Divine Proportion, found throughout the universe in places as diverse as the plant and animal kingdoms, whirlpools, cloud patterns, and spiral nebulae, as inspiration for two windows over looking the Hudson River. One, based on the interior of the chambered nautilus, represents Healing, and the other, based on its exterior, represents Hope.

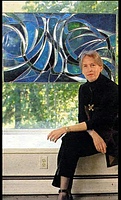

Harriet has long preferred the expanding spiral to the linear path, which for her symbolizes growth of the soul through experience. On the window sill in her studio, against the green light cast by a stand of bamboo, sits a chambered nautilus in its divine perfection, where she can see it whenever she lifts her head.