Palisades: Outpost of American Botanical History

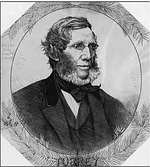

Stroll up Ludlow Lane past the old Niederhurst estate, and then follow the winding driveway to what is now the Lamont-Doherty campus of Columbia University, and you will be immersed in a myriad of local flora and fauna. My last walk disturbed a large family of wild turkey. As you go you may sense a landscape writ as palimpsest: the lives and homes of long-dead inhabitants now interwoven with those of current residents. Perhaps this is because the qualities that draw people to our spot on the Hudson remain much the same from century to century - not the least of which is its great natural beauty. One can only presume this is what compelled famed botanist Dr. John Torrey to make his summer residence on the high bluff overlooking the Hudson where the Lamont-Doherty campus now stands.

Torrey purchased the house as a summer residence in 1853 shortly after assuming the position of Assayer for the New York City Mint. Arriving by boat from the city, he was considered one of the first newcomers to the area. The house, sited on 1.5 acres, was surrounded by wildflowers in the spring and cooled by Hudson breezes in the summer. Torreyʼs wife Eliza Shaw Torrey died less than two years later and her headstone can still be found in the Palisades Cemetery. Torrey owned the house until 1865 and went on to found the Torrey Botanical Society, Americaʼs oldest botanical organization. Three other Palisades residents, Dr. Agnew, Mr. Park, and Mr. Winthrop Gilman were among the societyʼs earliest members.

Torrey is considered one of the giants of American botany. Two hundred years before the first champions of the now established native plant movement, Torrey made groundbreaking advances in the understanding of North American Flora. As pioneers ventured into the largely unexplored and wild terrain of the American west, Torrey analyzed, named and recorded thousands of specimens collected by explorer Major Long during an expedition to the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains in 1820. By 1826 Torrey presented an account of the collected specimens according to their natural order. This was the first treatise of its kind in America, and it established the study of botany in the Rocky Mountains. In 1836, Torrey was appointed botanist for a geological survey of the State of New York. In 1843, he published “A Flora of the State of New York,” a two- volume tome acknowledged as Torreyʼs most important work, and the first of its kind for any American state.

But Torreyʼs aspirations went further. He wanted to compile a general Flora of North America, and approached renowned botanist Asa Gray to be his associate. It was a hugely ambitious plan at a time when little was known about large tracts of the continent. But thanks to the opening of Pacific Railroad (Botany of the Pacific Railroad Survey), the Mexican boundary survey, and the expeditions of Stephen Long, Joseph Nicollet, John Charles Fremont, William Emory, L. Sitgreaves, Howard Stansbury, Randolph Marcy and Charles Wilkes, material to evaluate was becoming increasingly available. Indeed the exponential increase in the pace of materials submitted for analysis and inclusion proved to be the projectʼs downfall.

Torrey and Gray did manage to produced several volumes for their project between 1838 and 1843, but as Asa Gray wrote in an obituarial eulogy to Torrey on the occasion of his death in 1873: “From that time to the present the scientific exploration of the vast interior of the continent has been actively carried on, and in consequence new plants have poured in year by year in such numbers as to overtask the powers of the few working botanists in the country…The most they could do has been to put collections into order in special reports, revise here and there a family of a genus monographically, and incorporate new materials into older parts of the fabric, or rough-hew them for portions of the edifice yet to be constructed. In all this Dr. Torrey took a prominent part down almost to the last days of his life.”

Torreyʼs house no longer stands on its Hudson bluff – it was dismantled after a lightening strike in the 1890s - but structural timbers were reused in the building of 5 Closter Road. Torreyʼs land became part of Thomas Lamontʼs fine 1925 residence aptly named Torrey Cliff. In a pleasing circle of fate, in 1948, Lamontʼs widow gifted the estate to Columbia University - Columbia being the same university where Torrey was named Emeritus Professor of Chemistry and Botany in 1855, a trustee in 1856, and where he donated his extensive botanical library and celebrated herbarium of 50,000 specimens.

In another lasting tribute for posterity, the eponymously named Torrey Pine was officially “discovered” by Torreyʼs colleague Dr. Parry in 1850, the year California became a state. The species of yew-like evergreen Torreya taxifolia includes the stinking cedar (now listed federally as an endangered species although specimens exist in the Atlanta Botanical Garden and Arnold Aboretum), and the highly ornamental non-native Japanese Torreya.

Given Torreyʼs formidable legacy in the science of botany, as well as his stature as an early resident of Palisades, if a tree was to be planted for some future commemoration, one from the Torreya species might be an imaginative and meaningful candidate.