Native Plants of the Palisades

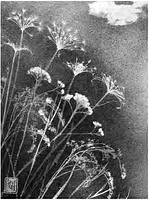

If you walk along the roads in Palisades, or through Tallman Mountain State Park this spring, you may see a smattering of wildflowers such as the odd jack-in-the-pulpit, or a stray trillium and feel as though something magical has been revealed to you. Imagine, though, what it was like not even a century ago.

Trout lilies and dog tooth violets carpeted the woods bordering the cow pasture; pink and white spring beauties grew in every space not already occupied by the “vast violet tribe”; great quantities of wild lily-of-the-valley clustered around the trunks of old hemlocks; jack-in-the-pulpit was ubiquitous; the woods were pink with wild geraniums; Dutchman’s breeches grew in “wild - torrents” among loose stones and in the black wood soil. And on April 15 of every year, Anna Gilman Hill invited her friends to her gardens at Neiderhurst to wonder at this natural abundance.

Anna Gilman Hill was one of Palisades’ noteworthy recorders of local floral ecosystems. She lived below

Torrey Cliff, home to the renowned botanist John Torrey who catalogued over 50,000 plant species native to New York and who published the Catalogue of Plants Growing Spontaneously Within Thirty Miles of the City of New York. Her own book, Forty Years of Gardening, long out of print, but available at the Palisades Free Library, and online from the HathiTrust Digital Library, recounts her long experience designing and maintaining gardens, both here in Palisades and at her summer residence, Grey Gardens, in Easthampton, New York. She allows us a glimpse into the undisturbed wild flora of Palisades.

Even at the time she was writing, she lamented the disappearance of native laurel, ferns, and arbutus that grew in profusion along the cliffs from Palisades to Fort Lee. People she called “marauders” came from the city to dig them up for sale. The only reason blood-root, violets, wood anemones, and Dutchmen’s breeches survived is that their bulbs go very deep, and their blossoms are so frail that it was not worth anyone’s while to pick them for commerce. In her book she laments the obliteration of yellow false foxglove and smooth false foxglove to encroaching development, but also delights in discovering a woodland colony of tiger lily - survivors from Torrey’s abandoned and overgrown hillside gardens.

The profusion of wild flowers that bloomed in every season along the cliffs, and in the meadows here can be hard to imagine. Even though Mrs. Hill uses slightly ecstatic language, she manages to convey a world that is hard for us to recognize. White wood asters grow in “hordes.” Dutchman’s breeches grow in “great drifts as far as the eye can see.”

This kind of plenitude no longer exists in any form except the human form. We have only ourselves to blame. Builders ruthlessly bulldoze woodland and meadows for developments. Well-meaning transportation departments line medians with soft, fast-growing Asian pears useless to native fauna, instead of slower growing and more durable native hardwoods. Amateur gardeners favor the large and flashy exotics to the more delicate native species. Herbicides and insecticides disturb the natural balance of ancient ecosystems.

In response to the stressors of human interference, the native plant movement was formed, based on the principles laid out by Lorrie Otto, a naturalist deeply influenced by Native American attitudes toward the natural world. Her governing idea, taken from Chief Seattle, was that “we do not inherit the earth from our ancestors, but rather borrow it from our descendants.” The movement’s mission is to identify local plant communities and to advocate for their restoration, preservation, and propagation.

Native plants as defined by the Native Plant Center in Valhalla, New York are those that occur naturally in the region and are suited to the climate and the soil. Another organization, Wild Ones, believes more specifically that native plants are any plant naturally occurring in a local ecosystem before the arrival of European settlers. Native plants form part of a cooperative environment or plant community that includes pollinating insects, animals, birds, and companion plants. Such ecosystems are finely structured, and function to sustain not only the immediate community, but also the larger one, such as preventing shore erosion or flooding.

These ecosystems are in turn part of larger eco-regions with similar environments that do not recognize state boundaries. To preserve ecosystems Wild Ones advocates using seeds and plants from local or regional sources at sites having the same or similar environmental conditions as those at the site of planting. Local ecotypes are genetically adapted to a region, help to preserve insects and animals that have co-evolved with them and depend on them for food and shelter, and preserve genetic diversity and integrity of native plants within and among species.

The USDA has published a map showing the boundaries of these eco-regions. Palisades is in Region 221, the Eastern Broadleaf Forest (Oceanic) Province that encompasses parts of Pennsylvania, all of New Jersey, the Hudson Valley, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, southern Maine and the region just west of the Appalachian Mountains. Plants from this area are considered “native.”

If you plan to garden with natives, it is as important to consider the entire ecosystem when designing or restoring an area, as it is to choose native or heirloom plants. For example, in 1975, landscapers were enlisted to restore dunes at the edge of the Los Angeles airport. Instead of native dune scrub, the seed mix contained seeds from the native sage scrub. As a result, the El Segundo butterfly, that had ranged over 3200 acres of coastline and that depends on dune scrub for its survival, became an endangered species.

It is also important to obtain local ecotypes from reputable nurseries, and not dig them up from natural areas unless those areas are areas slated for immediate destruction.

The plants should be designated nursery propagated, not nursery grown. Nursery grown plants are often dug from the wild and potted for sale. If you want to collect seeds from the wild, be sure to collect from as many different plants of the same species, and not just the biggest or showiest. This practice will help to insure genetic diversity.

Anna Gilman Hill was lucky enough to have a natural feast at her disposal, but for the rest of us interested in recovering our floral history one yard at a time, there are several excellent resources. To begin with, a number of organizations offer extensive information in gardening with local ecotypes, the nearest ones being the Native Plant Center in Valhalla and the Native Plant Society, Bergen/Passaic chapters. Both specialize in our eco-region.

Wildones.org is an excellent website with extensive educational tools, advice, and project tips. In Forty Years of Gardening, Mrs. Hill provides an excellent and thorough list of plants from her garden, their blooming times, and companion plants. More lists can be found at The Native Plant Society of New Jersey.

The New York Flora Association also offers lists of native plants by local ecosystem.

Plant sales at local flower clubs can be an excellent source of natives, such as The Garden Club of Nyack, usually around Mother’s Day, held at the Nyack home of Florence Katzenstein (845-353-0131);

The Garden Club of Irvington (plant sale at Lyndhurst, 914-631-4481);

Bartlett Arboretum (203-322-6971) in Stamford, Connecticut;

Wave Hill (718-549-3200);

The Wildflower Native Plant Center (at Winchester Community College in Valhalla) 914-606-7870;

Tappantown Historical Society (845-359-1923), held on the back lawn of the Manse;

Brooklyn Botanical Garden (the largest plant sale in the metropolitan area); and The Hudson Valley Seed Library which specializes in heirloom seeds, some of which come from local natives.

Imagine if in a few years from now, every April 15, we too can invite our friends to our homes in Palisades to view with wonder, the abundance of the natural world.